My research interests are centred around materials used for renewable energy generation (e.g. solar cells) and storage (e.g. reusable batteries). I use atomistic simulations techniques to predict the properties of materials and link the macroscopic observables (such as open circuit voltage or thermodynamic stability) with microscopic processes (such as electron capture or electron-phonon coupling). Our atomic scale models can be used to rationalise existing experimental observations, or guide future investigations. For example, it can explain why heat travels slowly through some materials or predict new materials for high-performance solar cells.

I use a range of simulation techniques including Density Functional Theory (DFT), Lattice Dynamics, Molecular Dynamics and Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials. I have a particular interest in structural phase transitions, thermodynamics and defect physics. My research has mostly focused on halide and chalcogenide perovskite materials.

Why Density Functional Theory?

DFT is an ab-initio (first-principles) method derived from quantum mechanics and can be used to predict material properties without experimental input (see, for example, this open access article).

When DFT is applied to crystalline materials it is often assumed that the atoms are perfectly static. However atoms always vibrate with heat. Even in their lowest energy state, at zero kelvin, they vibrate as a result of their quantum mechanical zero point motion. These vibrations are important to understand because they can have a significant impact upon the performance of a material and device. We combine DFT with other techniques such as lattice dynamics, molecular dynamics or machine-learned interatomic potential to describe this atomic motion, identify stable crystal structures, and predict finite temperature material properties.

Another assumption commonly applied to crystalline materials is that there is perfect translational symmetry - that there are no defects (missing or extra atoms). However a material always has defects (these are unavoidable due to the laws of thermodynamics), and some of these defects—when not managed carefully—can kill device performance. We combine DFT with careful analysis and post-processing techniques to model the impact of defects, and understand whether they are “killer” or benign.

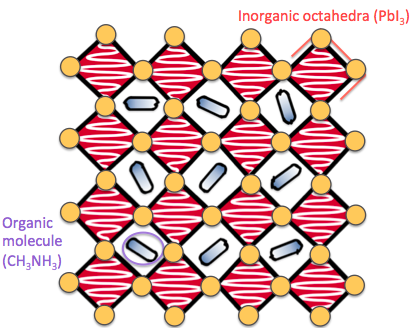

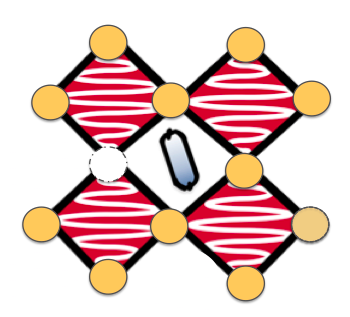

Why Perovskites?

Halide perovskites are a family of materials that have become incredibly popular over the last decade as they can convert sunlight into electricity efficiently, and have the potential to form more flexible, lightweight and cheaper solar panels than those currently on the market. However they have two large drawbacks: the best performing devices contain toxic lead, and they have a tendency to $^$ahem$^$ fall apart when exposed to moisture or air. We are currently exploring chalcogenide perovskites as an alternative, more stable, and less toxic material family.